Helene Aftermath: Guilt, gilt, and gold

Have you been feeling guilty?

Guilty when you enjoy the sense of community and camaraderie in your neighborhood? Guilty when you find a way to get to a neighboring town and take a warm shower? Guilty when you cook a hot meal in your own kitchen?

I haven’t spoken with a single person since Helene that hasn’t mentioned some kind of guilt. The scope of your loss doesn’t seem to matter—in the aftermath of a disaster, you will likely feel guilty.

Which indicates to me that this feeling isn’t personal. And yet—guilt is such a terrible feeling that it’s almost impossible NOT to take it personally. The intensity of the awful feeling seems to suggest that in order for it to feel this bad, it must mean there is something equally awful about you. Doesn’t the feeling of guilt mean that there is something you need to change about yourself? Isn’t the whole function of guilt to get you to change behaviors that aren’t in alignment with your integrity?

I would propose that survivor’s guilt has a different function altogether. We live in a devastated community. The web of our social ecology has been destroyed. It would be easy—understandable, even—for us to turn away from that devastation and tend just to ourselves and to our families.

But survivor’s guilt ensures that we do not. It’s about restoring the web of the community, not about something you’ve done or not done.

It’s not yours. It’s bigger than you. It’s not about you. It belongs to the collective.

Here’s the rub:

If you take the guilty feelings personally, you might find yourself comparing yourself to others, undermining your own wellbeing with critical thoughts, or beating up on yourself for your luck or privilege. You might find yourself trying to change behaviors —like resting or taking time for self care—that are actually helpful to you. Unfortunately, these responses will harm your health, and they won’t repair the community.

If you take the feeling of guilt personally and try to escape the suffering by numbing it out, pushing it away, or distracting yourself, that’s not going to help either (as a mentor once told me: uncomfortable feelings don’t go away when you sidestep them. They do pushups.)

I think of those two responses as gilt guilt. It might look right on the surface, but doesn’t go all the way down. It doesn’t address what needs to be addressed.

Gilt responses to guilt are completely understandable because guilt feels so bad. In hedonic terms (pleasure, comfort) guilt is an awful sensation.

But in eudaimonic terms (from the greek eu, pleasure, and daimon, spirit—the pleasure of the spirit) guilt itself can be both helpful and good. Aside from the discomfort of the feeling, what it is trying to do is call your attention to something that matters.

Because guilt has gold in it, too. It can be what they call an “FGO”—an F’ing Growth Opportunity. Feels bad, is good. If you can attend to the feeling of guilt without using it to shame or judge yourself, guilt will tell you how to act on what matters.

Guilt + your values = gold.

For example: If I am feeling survivor’s guilt because I just sat with a client who lost her home and I have a completely intact home to return to tonight, I could try to push that feeling away. I could use it to belittle myself and feel shame about my own experience. Or, I can ask myself: what does this feeling of guilt want me to know about what matters to me? What could it tell me about my place in rebuilding the community web?

When I consult my own values, I know that whatever we rebuild, I want it to be more equitable, more resilient, more creative, more inclusive than it was before. Then, the feeling of guilt turns me toward the problem instead of against myself. It causes me to get curious about actions I can take in my community that are equitable, resilient, creative, compassionate, and inclusive.

When I sit with these values instead of taking the guilty feeling personally, I can recognize that my intact home is a resource for the community. I can shelter friends, family, and responders there—which will help me lean into inclusivity. I can cook nourishing meals there— leaning into resilience and compassion. I can host gatherings to build a sense of community, creativity, and equitability.

This doesn’t mean that I should be spending every moment in a frenzy of positive engagement. There will be mornings of crying, days of staring into space, times of connecting with family and friends and taking care of myself.

But it does mean that if I am suffering with painful feelings of survivor’s guilt, I don’t have to take it personally. Instead, I can use it to clarify my values and direct my feet toward what I would like to happen next.

In a former lifetime I heard Michael Meade say that when the kingdom falls ill, the answers come from the edge. Every person finds their thread, and they carry that thread back from the edge to the center, and the center is rewoven.

It takes all of us to stitch the web back together. Your guilt does not belong to you—don’t take it personally. No single one of us could ever do everything that needs to be done.

But there is gold in the guilt. It might just be the gentle nudge that helps you find your own thread, the thread that will weave you back home.

Our next depth storytelling event, a benefit for BeLoved Asheville, will be taking place October 29th. Come and be held by story—sometimes the back of an old story is broad enough to carry what is too heavy for us alone. Join us from anywhere in the world—a recording will be provided for registrants who can’t attend live.

Helene Aftermath: Accept Help

Benjamin Franklin famously wrote that the best way to make a friend was to request a favor. There is something about the vulnerability of requesting help that touches the human heart.

And yet so many of us seem to struggle with accepting help. Whether it is a fear of inconveniencing another person or social conditioning rooted in extreme individualism, we seem to have difficulty allowing others to give us what we need.

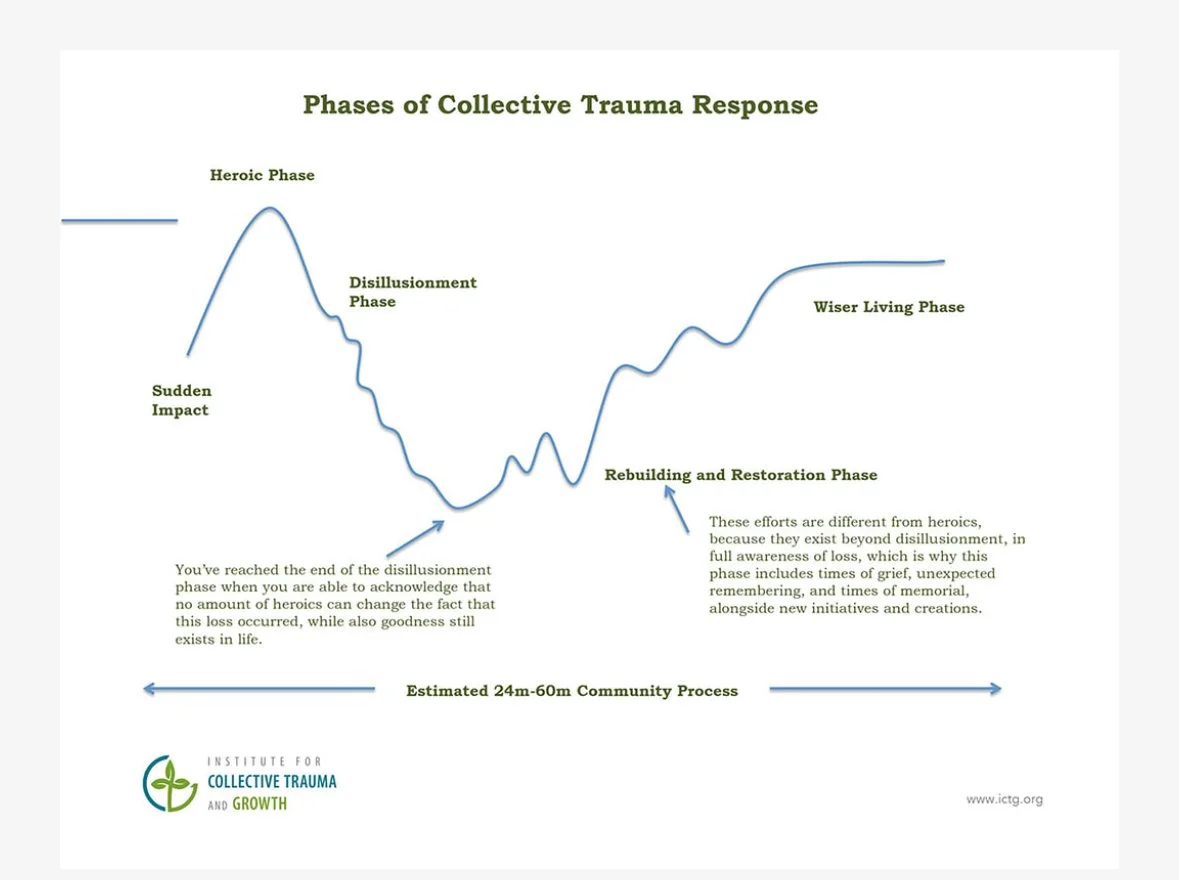

We are in a moment right now, in the aftermath of Helene, that some trauma response models call the Heroic Phase. In the heroic phase, we are capable of extreme efforts, both physically and emotionally, as we respond to disaster and trauma.

It’s important to know this for two reasons:

1) During this phase, giving and accepting help creates strong trust and relationship within the community. When we are feeling heroic we need to give. To give, we need receivers. Heroic efforts to help that are thwarted at this time tend to result in emotional collapse.

2) This phase will end. As we continue to engage in prolonged recovery efforts, our hearts will break again and again and the initial adrenaline-fueled power of the Heroic Phase will ebb. It’s helpful to know that this is coming and to prepare for it. And, if we have cultivated strong community relationships during the Heroic Phase, those relationships will be there to help all of us get through the disillusionment and heartbreak.

So, dear members of this community, if you can give, give. If you don’t live in the area and have resources to donate, here are some wonderful local organizations that are in need of your help (scroll down in the article to see the local organizations). It’s a marathon, not a sprint, so if there is one that speaks to your heart a small ongoing gift would be more helpful than a large one-time donation. If you live in the area and volunteering would help you process your experience, there are opportunities for volunteering here.

But equally important: if you are in the position to receive help, please do. It will benefit the mental health of the person offering help. It will strengthen relationships in our community. And most importantly, the healthier and more resourced you are, the healthier we all are. Because individualism is a myth. What we are is interdependent.

Over the weekend I realized that several of the organizations our community donated to through the storytelling project have come to our aid. World Central Kitchen is feeding people throughout Western NC. Care International is sending resources. RiverLink will be on the front lines of cleaning and healing our rivers. How humbling and inspiring to see, in this microcosm, the way that giving and receiving help weaves the web of community.

Helene Aftermath: Watching the world

Last night as I sat wakeful beneath my open window, a chorus of frogs began to sing me to sleep. This morning, gathering what flowers remain in my wind-torn garden, I was startled by a cardinal—the first songbird I’ve seen in over a week. There were hawks after those winds, though they looked shocked too—but no songbirds. Now they are coming back.

We humans are not alone in our loss—animals, trees, ecosystems have been devastated and are also finding their way to recovery. But one of the only things my scattered brain has been able to rest on today is the sight of one of my favorite trees, a maple the storm spared, turning slowly golden through the window of my counseling office. That tree alone holds my frantic mind still.

It reminds me that in old stories of floods, often the very first signs of hope are the reappearance of birds, the blooming of branches. I have learned to watch what nature does and to emulate it as closely as possible, given that it’s the oldest regenerative system we can observe firsthand.

One of the first things I am seeing is tiny plant seeds germinating in the mud. Their roots will hold the mud in place as they drive down and in, and in some cases, these pioneer plants will serve as bioaccumulators, taking in and secreting toxins from the soil so that a greater diversity of plants will be able to germinate in the next generation.

How can we begin to hold ground, hold our place, even as we metabolize the toxins that have been left in the wake of the storm? And how might we build back in such a way that the coming generations are even more diverse, more resilient?

I have seen, too, in the humans around me, that those who have been able to take action are faring better than those who have not. There’s something about DOING, metabolizing all of that worry and fear and sorrow into action, that helps us. Picking up sticks from the ground, carrying buckets of water, delivering food, shoveling mud. Or sitting in the sunlight and humming, shaking, dancing.

Moving our eyes across news does not count. It is important to think and to connect resources and to plan—and thank you to those who are doing it! But even this toxic wash of mud left in the wake of the floodwaters is not sitting still. It’s cracking, drying, sprouting, transforming. We need that, too. What is beginning to take root in you that holds you, however incrementally, together? How are you—literally—moving through this?

Here are some ways to volunteer: https://www.handsonasheville.org/

Today, in between sitting with clients, I went outside with a poem and walked. This is the poem I walked with today. It has helped me put language to the grief I feel for places I love that are changed forever. The lovely curve of Chimney Rock gorge. Sweet Swannanoa. My ancestral home, Marshall. May the words of this poem help you root your grief in the large arms of all who have grieved beloved cities before.

The God Abandons Antony

When suddenly, at midnight, you hear

an invisible procession going by

with exquisite music, voices,

don’t mourn your luck that’s failing now,

work gone wrong, your plans

all proving deceptive—don’t mourn them uselessly.

As one long prepared, and graced with courage,

say goodbye to her, the Alexandria that is leaving.

Above all, don’t fool yourself, don’t say

it was a dream, your ears deceived you:

don’t degrade yourself with empty hopes like these.

As one long prepared, and graced with courage,

as is right for you who proved worthy of this kind of city,

go firmly to the window

and listen with deep emotion, but not

with the whining, the pleas of a coward;

listen—your final delectation—to the voices,

to the exquisite music of that strange procession,

and say goodbye to her, to the Alexandria you are losing.

-C.P. Cavafy

May we all be graced with courage, may we all find support in the ancient resilience of the natural world even as we grieve the exquisite music of what we have lost.

Helene Aftermath: Belonging to Ourselves

Some beautiful things I have seen lately: People driving around with trucks loaded with food and water, stopping to ask anyone they see if they need anything. Restaurants and food trucks grilling up free meals and serving them out to anyone who is hungry. Neighbors posting information so that those without connectivity can be connected with resources. My exhausted brother, who is organizing rescue efforts from Greensboro, making a special trip out to us to make sure we have enough drinking water, food, and gas.

I had a long conversation this morning with a client who has lost her home. We read the poem below together and grieved the place that held her life and her memories, her plans for the future. And she told me that now the faces of her children are “the bright home in which I live.” She asked me to share this, here.

Because the pain of holding both at the same time—the heart-rending grief of losing “the bright home in which I live/ where I ask all my friends to come” even as she celebrates her family’s survival, knowing “how easily the thread is broken/ between this world and the next” —it’s enough to tear a person in two if we can’t find enough backs to carry it.

We are asked to hold both, now. We need each other so that we can get big enough to do it. It made me think this morning of how we insulate wires with a plastic coating to keep them from sparking each other. All of our insulation is lost, right now. We are touching wire to wire. And sometimes stripping away the insulation of comfort and safety means we feel love and appreciation for our family, our neighbors, the beauty in the world more intensely than ever. And sometimes it means that sparks fly and ignite and grow into rage and fear and scarcity-driven cruelty.

I awoke

this morning

in the gold light

turning this way

and that

thinking for

a moment

it was one

day

like any other.

But

the veil had gone

from my

darkened heart

and

I thought

it must have been the quiet

candlelight

that filled my room,

it must have been

the first

easy rhythm

with which I breathed

myself to sleep,

it must have been

the prayer I said

speaking to the otherness

of the night.

And

I thought

this is the good day

you could

meet your love,

this is the black day

someone close

to you could die.

This is the day

you realise

how easily the thread

is broken

between this world

and the next

and I found myself

sitting up

in the quiet pathway

of light,

the tawny

close grained cedar

burning round

me like fire

and all the angels of this housely

heaven ascending

through the first

roof of light

the sun has made.

This is the bright home

in which I live,

this is where

I ask

my friends

to come,

this is where I want

to love all the things

it has taken me so long

to learn to love.

This is the temple

of my adult aloneness

and I belong

to that aloneness

as I belong to my life.

There is no house

like the house of belonging.

by David Whyte

This is the black day someone close to you could die. This is the good day you could meet your love. When you can, stretch enough to hold both. When it feels impossible, rest.

I offer the guided meditation below for those of you who are feeling your brain spinning and sparking, unable to sleep, caught in cognitive loops. Sometimes the most restful thing when that happens is to reconnect with the wisdom of the body.

(Bodies are all different, and if the meditation does not match yours, please imagine your inner world infused with the capacities described regardless of the form they take, and accept my apologies for my flawed language.)

Helene Aftermath: The two children

Hello, all—I would like to share an old story with you today. I have been noticing in myself, my friends, my clients, that in the wake of crisis there are several normal, organismic responses that sometimes we judge ourselves for having. Three that the story explores are feeling a need to escape/get to safety, a need not to see the bad things but instead to experience only wonder, beauty, and helpfulness, and feelings of overwhelming grief and rage. In the story, all of these responses have their place.

I invite you to find inside of you where all of these things are happening, and to offer self-compassion to every aspect of these responses. If we can treat our normal responses with care, they don’t have to come out sideways in acts of aggression against others or internally as self-sabotage. When we work with things that happen imaginally, as within a story, we don’t have to suffer the heartbreak of actions we regret.

Had the ones who left not left, everyone would have starved. Had the sister not seen wonder, the brother would have been lost within himself. Had the brother not felt his anger, he and his sister would have been helpless and without resources—and the village would not have changed in the aftermath of this story, would not have learned anything, would not have deepened.

Once I heard Martin Shaw tell a story and conclude it with this sentence: “See what happens in your own heart when you trade growth for depth.”

I am feeling in my own heart these days what happens when I trade growth for depth. There are things that were “normal” a week ago that I do not wish to experience as normal again. There are relationships I have built and ways of being I have cultivated in the wake of this flood that I hope I can continue to nurture. There are things I need to learn, here, that may change the shape of the village.