Epigenetics and Empathy

By Lissa Carter, LCMHC

These are hard times. Many of us are exhausted. For months, we have been sitting with the shadow: the unhealthy coping mechanisms that emerge when we spend too much time alone. The addictions that come out of the woodwork when we are under stress. The relational patterns that tax the family system under lockdown. The projection of our physical/financial/emotional fears onto others, the way we frantically search for someone to blame for all of the changes. And now we are sitting with the collective shadow of systemic racism.

In this environment of scarcity and exhaustion, it can be so very easy to put the blinders on and muscle through. To blame some Other person or group of people whose thinking is not like our own, or whose actions defy our understanding. To step out of empathy and into righteousness.

But as we know from decades of research, humans who are connected creatively and empathetically fare better than humans who have shut down those areas of the brain that foster connection (I wrote more about this here.) When we step out of empathy, we abdicate the very skill set that is most likely to lead us toward long-term survival.

Empathy is threatened when fear shuts down our willingness to connect and puts us in fight-or-flight. So one key skill for strengthening empathetic response is paying attention to context.

Empathy and Attribution Error

When we are in grief, or rage, or overwhelm, the part of the brain that makes rational, logical decisions is less accessible. Think about a woman who has lost her only child. If she falls to the ground in the midst of the funeral and begins to tear the floral arrangements into pieces, how do you respond?

a) that woman must have mental problems or

b) that woman is consumed by grief, my heart goes out to her

Most of us respond with “b”. When we understand context, we can attribute a person’s behavior to the context rather than to the intrinsic character of the person.

But what if you didn’t know the context? What if all you saw was a woman tearing up expensive floral arrangements and screaming?

Chances are, in that case we might erroneously think this woman is a disturbed or destructive person. We would be committing an all-too-human mistake known as fundamental attribution error.

The fundamental attribution error is the tendency to attribute our own actions to context (I am speeding because I am late to pick up my daughter, and she must be so worried!) yet to attribute others’ actions to innate character flaws (that guy is speeding because he is a jerk). We commit attribution error when we disregard context, and evaluate behaviors as though they occur in a vacuum.

Assuming that someone must be fleeing instead of jogging because he is wearing a style of shorts I don’t associate with jogging is an attribution error. I can address this error in myself by pro-actively seeking out the stories and life experiences of people who think/live/speak differently than I do. This starts a positive feedback loop in which my openness to others’ perspectives increases my understanding of and empathy for others, and my increased empathy and understanding makes me more likely to listen openly to the experiences of others.

But there is another layer to consider here.

Empathy and Epigenetics

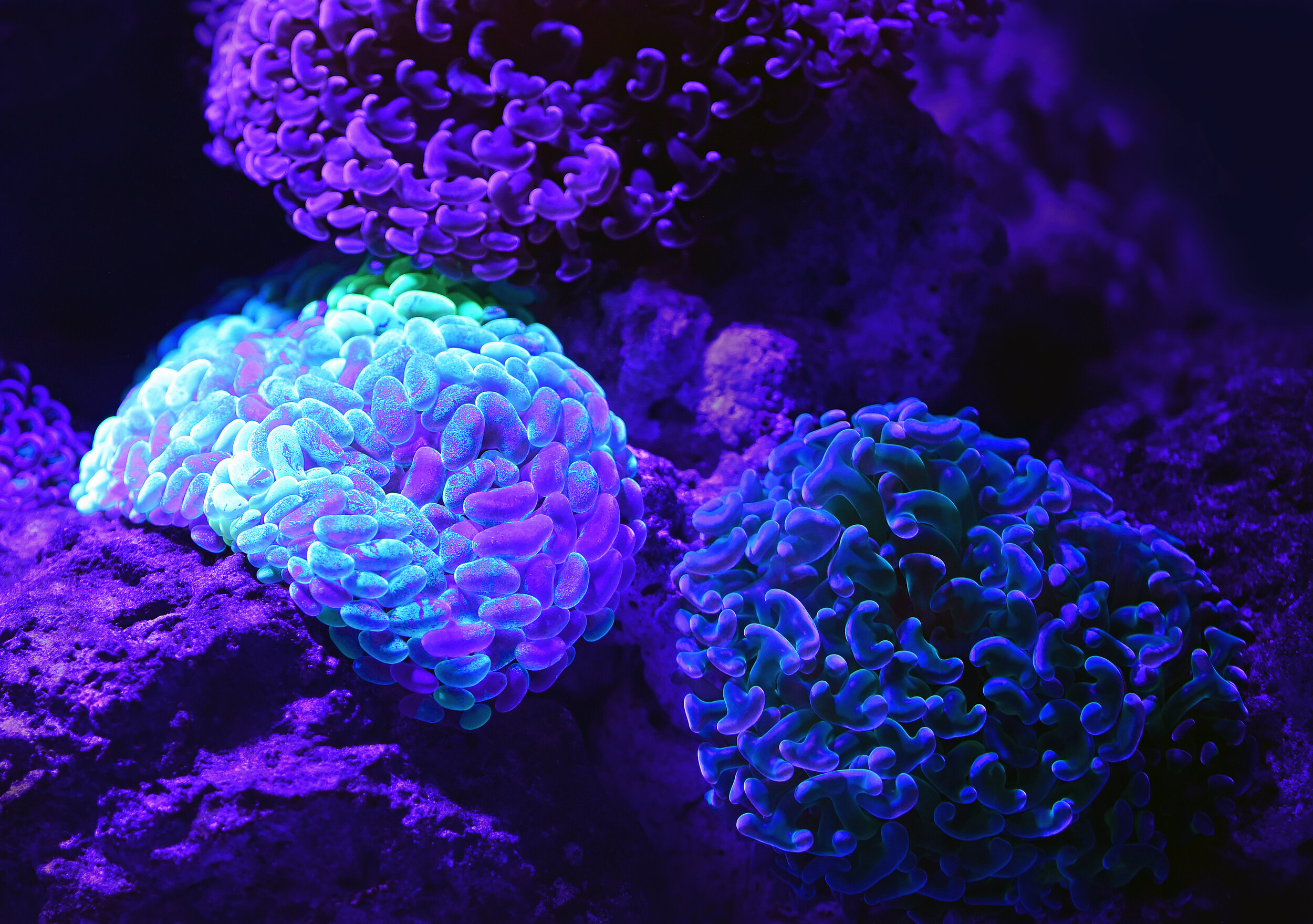

Context does not only occur in the present moment. We have learned through recent studies in epigenetics that the environmental context a person lives through can leave genetic markers that impact the DNA expression of two generations of descendants. (read more about this here).

This means that a woman who survived the holocaust might have a granddaughter who, never having met her grandmother, struggles with high anxiety and hypervigilance. A grandfather who fought in the war might have a grandson who startles at every loud noise.

So consider this: the context that tells me the grieving mother is behaving appropriately is the death of the child. What about a historical context in which generation after generation has experienced brutal separation from their children? This is new research, so we can only begin to grasp the ramifications on a people that have experienced generation after generation of atrocity, from kidnapping to forced labor to family separation to lynching to profiling. How might it change your ability to empathize with the anxious action of an individual to understand that behind that action are several generations of traumatic experience?

If we truly make the effort to understand not only the individual but also the historical context of an individual’s behavior, we can strengthen the muscle of empathetic response rather than reacting out of fear or anger.

Building your Empathy

So far, we have learned that you can actively build your empathy by seeking out the stories of people who have a different perspective and life experience than you do. You can increase empathy and avoid attribution error by pro-actively observing both the present-moment and historical context within which people act.

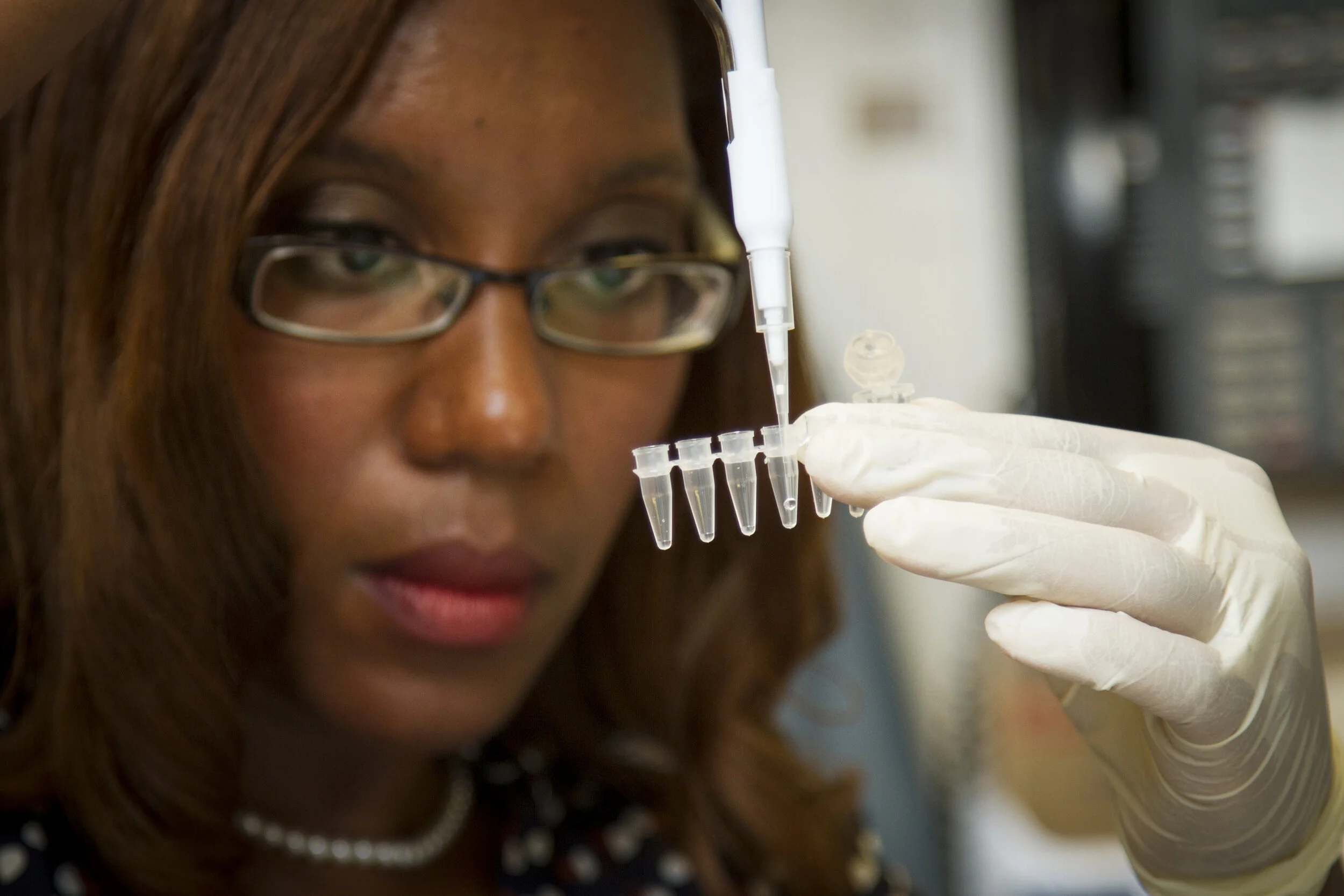

But there’s one more fascinating way that epigenetics can inform empathy. In studies of mice, scientists were able to demonstrate that adult mice— those that had directly survived trauma as well as their descendants—who were given healthy, stress-free environments to live in were able not only to heal their own traumatic expression, but also to change the epigenetic markers they passed down to their children. From this we can infer that it may be possible to heal entire chains of ancestral trauma within the space of one generation.

But to do so, we need to create a healthy, stress-free environment for the survivors of ancestral trauma.

What does an empathy look like that takes as its mission the active creation of a healing environment for our brothers and sisters? I don’t have the answers, but I suspect it looks like picking up the bulk of the educational and emotional labor. I suspect it looks like offering resources that have been accumulated through privilege to provide scholarships, to build platforms and networks for unheard voices and undervalued perspectives. I know that it means (and I hope this goes without saying) eliminating the primary stressor of racism in the day-to-day experience of this generation. Or, if that is too much to hope for, in the day-to-day experience of the next generation. I know it looks like asking ourselves, every day, How can I use my resources to ease the burdens of others?

Action Steps

We can acknowledge and make room for the very real intergenerational grief and mourning that needs to happen. We can read up on the history and context of current events. We can educate ourselves about systemic racism. We can refrain from pointing fingers at individual actions until we understand the context in which they are happening. We can remember that when a person is experiencing deep grief or rage, it is not a time to be logical or engage in rational debate. It is a time to listen, provide empathy, and create a safe space for emotional processing.

Empathy isn’t something we have or don’t have. It’s something we practice, and we practice it by listening, by creating space in our minds for the perspective of others. We know from the work of Stephen Porges that social engagement is our most adaptive human response. There is too much at stake to be working with anything less than our most adaptive human response.

I have learned, from the privilege of witnessing my clients every day, that if we lean into our empathy, remarkable transformations are possible. I have so much hope that we can love ourselves and our neighbors through this. I have deep hope that we can emerge more empathetic, more deeply connected, on the other side.

______________________________________________________________________________________

Self-talk Saves the World

By Lissa Carter, LCMHC, LCAS

Hey, PSA: If you have been irritable lately, if you have been lashing out more frequently or finding yourself feeling keyed-up, judgmental, and selfish, there’s a reason for that.

Collectively, we are experiencing a decrease in oxytocin and an increase in cortisol.

Oxytocin is the bonding hormone released when mothers nurse their babies, when partners make love, and when friends hug. It also functions as a neurotransmitter that aids us in feeling a sense of connection and belonging. When we do not hold each other, when we do not engage in warm and caring physical interactions, our oxytocin levels diminish.

Cortisol is a hormone that, when released, takes us out of connection and drops us into fight-or-flight. When we feel fear about our own physical health or the survival of our family, when we ruminate on the state of the economy, the planet, and the species, the amygdala perceives a threat and sends signals that increase cortisol. When cortisol surges, so does vigilance, violence, and reactivity.

Over time. a chronic reduction in oxytocin and uptick in cortisol will shape a personality that is less connected, empathic, and creative and more vigilant, reactive, and avoidant.

Given that close connection has been our best evolutionary strategy, these neurological changes do not bode well for a successful response to the crises our species is facing. We do not do our best thinking in fight-or-flight. We do our best thinking when we are connected, aware, and focused not only on our own survival but on a more allocentric sense of the survival of the whole.

So what is a socially responsible mammal to do? On the one hand, we need to care for each other by maintaining careful social distancing. On the other, we know that abstaining from connection can shape personalities that are less empathic and more reactive.

Kristin Neff’s research on self compassion points one way out of this double-bind. It turns out, the microcosm of your relationship to yourself generates oxytocin and cortisol just the way your relationships to others do.

This means that even as you practice social distancing, you can reshape your neurochemistry by relating to yourself differently.

Let’s create a completely hypothetical situation to demonstrate how this works.

Let’s say, in this 100% made-up scenario, that I’ve been noticing myself acting selfish. Specifically, I’ve been responding to feelings of scarcity by hiding chocolate from my children. When I notice myself doing this, I respond with self-castigation: why am I hiding the chocolate from my children? I am a self-obsessed monster who doesn’t care about anybody but herself. I am just like that terrible, terrible man in Anne Frank’s diary who stole food from children in the night!

My amygdala hears this self-censure the way it would hear anyone else yelling at me, and prepares my body to release cortisol and adrenaline in preparation for a fight.

Here’s the problem: I am now disconnected from my empathy and creativity and plugged into my shame and fear. These two states are reciprocal inhibitors—if I am locked in shame and fear, I am more likely to behave selfishly, not less.

Fight-or-flight turns us inward; it removes the focus from the well-being of the whole and absorbs us in relentless self-protection. I cannot access empathy from this place.

What if, instead, I were to notice myself hiding the chocolate and smile the way I smile indulgently at a dear (if quirky) friend? What if I told myself tenderly “wow, you must be feeling really afraid to do something like that. This is really different than who you want to be, so you must be super uncomfortable.”

Now, instead of releasing cortisol, I’m generating oxytocin. Instead of shunting all of my consciousness toward fight-or-flight, I am maintaining awareness, empathy, and a connection to logical, creative thinking. From this place, I am far more likely to take a deep breath, remember who I want to be, and call the kids into the kitchen for brownies.

This works whether you believe it or not; it’s in the wiring. Even if you feel silly hugging yourself and telling yourself you’ll be okay, your brain will still generate oxytocin as you do it. And your brain doesn’t care if you’re a lifelong pacifist; if you continue to criticize and judge yourself your cortisol will spike and you’ll become more prone to lashing out.

We are, individually and collectively, sitting with the shadow. All of the convenient distractions and helpful Others to project our issues onto have vanished, and we are forced to face uncomfortable, distressing truths about ourselves that we’ve always been able to dodge before.

If we are going to survive this with our empathy intact, we face a twofold task: we must learn how to relate to ourselves with compassion even as we come to terms with unwanted, shadowy parts of ourselves we would prefer to avoid.

Shadow work isn’t easy, but it is simple. In a nutshell, it looks like this:

Catch yourself doing or saying something that you don’t like, take a deep breath, and excuse yourself. Don’t let yourself get caught in justifying your actions or blaming someone else (even if they are being shadowy too!)

Let yourself notice what it feels like in your body. As these thoughts and emotions swirl around you, what does it feel like beneath your toenails? How fast is your heart beating? What colors are showing up behind your eyelids?

Imagine a loving, compassionate friend laying an arm across your shoulder, or squeeze yourself in a hug. Breathe. Let the emotions and thoughts get as big and painful as they are going to get. Let yourself see and feel the thoughts and actions that are out of integrity, notice what they cost you, and refuse to abandon yourself.

Rock, squeeze, breathe. Listen to what these emotions and thoughts are trying to tell you. Offer yourself compassion for the discomfort you are feeling, and stay present until the worst of the painful thoughts and feelings has passed.

When you feel ready, ask yourself what will help you step back into integrity. Then do that.

If we can maintain tender connection to ourselves even when we are uncomfortable, we begin to learn how to stay. If we can stay—connected, aware, kind, and thoughtful—even in the middle of big scary uncomfortable emotions like shame and scarcity and fear and loss—we might just get out of this okay.

So that’s our work, alone in our “alchemical huts” as Martin Shaw has described our little units of quarantine— to befriend ourselves as we are, not as we wish we were. To tend the connectedness and belonging of the one relationship we all have access to, the relationship with ourselves. To not turn away when we do something scary or gross or icky, but to keep a compassionate witness.

The more familiar we are with this territory in ourselves, the better we can navigate it out in the big, shadowy world. We’re going to need your ability to face the unattractive parts of human nature. We’re going to need your oxytocin supply as we face greater and greater storms of human vigilance and reactivity.

As Dr. Steve Aizenstat says, it’s the intolerable image that holds the healing. If we can sit with that intolerable image, if we can face it instead of pushing it away, we will learn how to maintain relationship under even the most difficult circumstances.

If you can learn to stand yourself in your moments of deepest ugliness, you can learn to stand anyone’s ugliness without losing your ability to love. And love is what makes us a species worthy of survival. Love is what will get us through this.

Safety and Sound

By Lissa Carter, LCMHC, LCAS

There are two practices I am leaning into in these disorienting times, and they are not the practices I would have assumed would be most helpful. Not my art journal, not my breathing practice, not setting “worry timers” and only worrying within those allotted minutes.

All of these practices are wonderful, and they are adding much-needed structure to my days, but they aren’t the two that truly ease my heart and mind.

The ones that are really helping?

1) Listening to the birds in the morning and singing with them.

2) Spending time with plants.

The more-than-human world is so helpful right now, both in finding a perspective that is not overwhelming and in generating genuine joy and renewal. We are mammals; we feel safe when we can touch each other and hear each others’ voices. Although we are wise to physically distance right now, it is important that we find other ways of getting our need for connection met. Why? Because when we feel unsafe, we are less kind to ourselves and to others.

I am finding that connection in the tenderly blooming chickweed, the softness of mosses, the strength of the spine of the maple tree in my backyard. I am finding it in the ululating notes of the birds that celebrate every single dawn.

Lately I have been singing with them. There is science to back this; singing, chanting, and sounding stimulate the vagus nerve and create feelings of safety. Whether it is in your shower, on the phone to your friend, or softly to your sleeping child, singing is a beneficial and balancing practice right now.

The better we care for ourselves and meet our safety needs, the more available we are to help others when they need us.

If you are feeling disoriented, know that this is the right way to feel. Place a hand on your heart, breathe deeply enough to lift the hand, and offer yourself some compassion for these difficult times you are living in. Find a tone that seems to resonate with your heart, and hum. Hum gently, but enough that you can feel your heart vibrate with the sound. Stay in this humming practice until you can feel something shift. Sometimes this brings tears and sometimes it brings a sense of strength.

I am in this with you, and I wish you strength, softness, and self-compassion.

7 days of dreaming: deep listening

Here we are, on the final day of this journey. I hope you will continue to pursue dream work if you found anything of value here! If you are interested in further offerings from Inner Light Counseling Collective that incorporate dream work, contact me through the form below and I’ll reach out when we hold dream workshops or groups.

…And now let’s move on to our final dreamwork skill, the skill of deep listening.

Dreamwork Skill #7: Deep Listening

Imagine that a child you love very much comes to you sobbing so hard he cannot breathe. Once you have soothed and calmed him, he begins to tell you a story of how he was playing with friends on the playground, but another kid he did not know came and pushed him down.

Because of your attachment to this child, you might get angry and march over to the playground to confront that bully. You might feel overwhelmed and try to dismiss the child’s sadness, tell him “stop crying, it’s okay now” to try and make the pain go away. It is very hard to see the ones we love hurting.

And yet, if we can tolerate the distress of our own anger or sadness, we can sit with this child and listen to his story. We can listen deeply, noticing his feelings, his thoughts, asking questions about what this means for him, working with him to make a plan about how he wants to handle situations like this one in the future.

This is exactly the way we want to listen to our own dreams.

Deep listening means you don’t only listen for what is there, but what isn’t. If a friend tells you she is thrilled about her new job but describes it in vague, lackluster tones, you probably wouldn’t take this at face value. You would ask her what’s bothering her, and why her voice sounds so unenthusiastic when she claims she is delighted.

Similarly, if a dream shows you an empty room, you might get curious about why the furniture is absent. If a dream shows you scene after scene of night and darkness, you might wonder where the light is. If most of your family shows up again and again in your dreams but one family member does not appear, you might get curious about this.

Deep listening also means that you follow motifs and patterns. In listening to the child tell his story of bullying, we might ask if this has happened before, or if it happens at other playgrounds. In our dreamwork, we do this pattern-thinking by tracking certain symbols, characters, or settings that emerge again and again in our dreams.

Finally, we when are really listening, we want to make sure we are getting the whole story. We ask questions to illuminate our understanding of the situation, try to understand its origins and also collaborate to find solutions. In dreamwork, this might mean actively imagining what the next scene in your dream might have been had it continued. It might mean noticing the opening scene of a dream and wondering what happened immediately before to create this circumstance. It might mean “taking an assignment” from the dream, whether this is something as simple as wearing a shirt the color of the shirt your dream-self wore in your dream, or as complex as watching your dream-self behave passively and “taking the assignment” of acting more assertively in waking life.

Does all of this sound like a tremendous amount of work?

The reason I go to all of this effort with my own dreams and with the dreams of my clients is simple: it bears incredible fruit. Personal work that is too painful or hard to do in waking life feels much more accessible when we look at it with the distance that a dream creates. It is easier to notice the negative patterns of a dream-self than it is to observe our own patterns, because it feels less personal.

In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, this ability to take a step back from our own thoughts and view them at one remove is called defusion, and it is a core skill for psychological flexibility and resilience. Our dreams give us the opportunity to practice this skill daily!

Dream Practicum

The Spaghetti Restaurant

i. a woman and man are taking their children to a spaghetti restaurant. The owner says he is closing the restaurant down. The man is sad about this, but the woman is she is glad because she used to work here and they treated her poorly.

ii. the children are serving themselves from a buffet of spaghetti dishes. There are little spheres of tightly-wound spaghetti and meatballs, but every time the woman goes to serve herself there is no food. She begins to feel frustrated, angry, and forgotten.

iii. The woman tries to get a drink but the doors to the kitchen, where the ice machine is, are locked. She is screaming and pounding on the kitchen doors when a passing server gestures to a station nearby where pitchers of ice and water are all prepared, just waiting to be poured.

Pause here for a moment and imagine this is your dream. Pick a dream skill and practice it: tracking the dream self, finding the emotional signature, finding compensating characters, replacing symbols with their associations for you. What assignment might this dream have for you?

Deep listening means having a conversation with the dream that goes a little deeper than simply applying the dreamwork skills. If this dream were a person trying to get your attention, what message would it have for you? How might you respectfully respond to this message?

When the dreamer listened deeply to this dream, here is the narrative that resulted:

A Place Where I Can Be Fed

i. A part of me that is passive and a part of me that is decisive are both trying to get fed. The part that is decisive is sad when there is no nourishment, but the part that is passive feels glad because it feels like a punishment, and this feels like justice.

ii. Parts of me that are playful and a little bossy are able to feed themselves very well even though I am so tightly-wound and over-controlled. But the passive part of me can’t get nourished and feels so angry, even though life is presenting so many options to choose from. This feminine part that wants to receive is starving.

iii. . This passive part is trying to stay alive but cannot find entry into the place where creativity is. This part of me is screaming for attention and trying to burst through the part of her that keeps others out. A part of me that knows how to take care of me points out a source of nourishment that requires the passive part of me to take action and serve itself. Somehow I had never noticed that there is nourishment for me if I am willing to serve myself instead of waiting around for others to let me in.

When the dreamer took the time to listen deeply to this dream, she noticed that she was the only female character in the dream. Every other character—-the owner, the server, the children, the cooks—was male. As she allowed herself to grow curious about what assignment this dream held for her, she noticed that although the “masculine” parts of her had no trouble getting fed, the “feminine” part of her could not receive nourishment because it was unwilling to serve itself.

The assignment she created from this dream was to allow herself to ask for and receive the aid of others in the realm of her life that bore the emotional signature of the dream, which was her relationship with her career. She was surprised to discover that when she requested help from her co-workers, they were thrilled to offer it.

This dream is shared with permission; some details have been changed to protect confidentiality.